The Hospital in the Oatfield

The art of nursing in the First World War

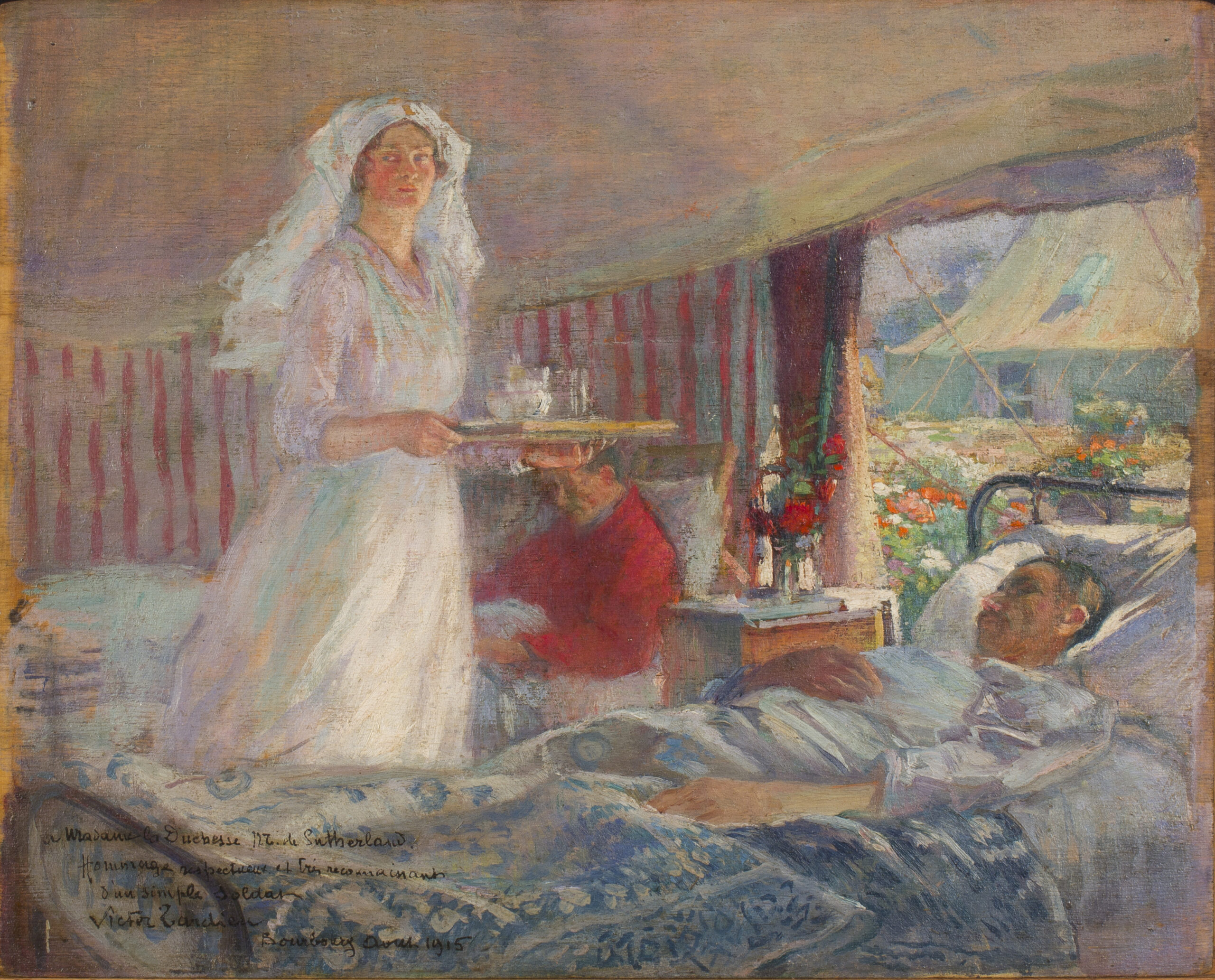

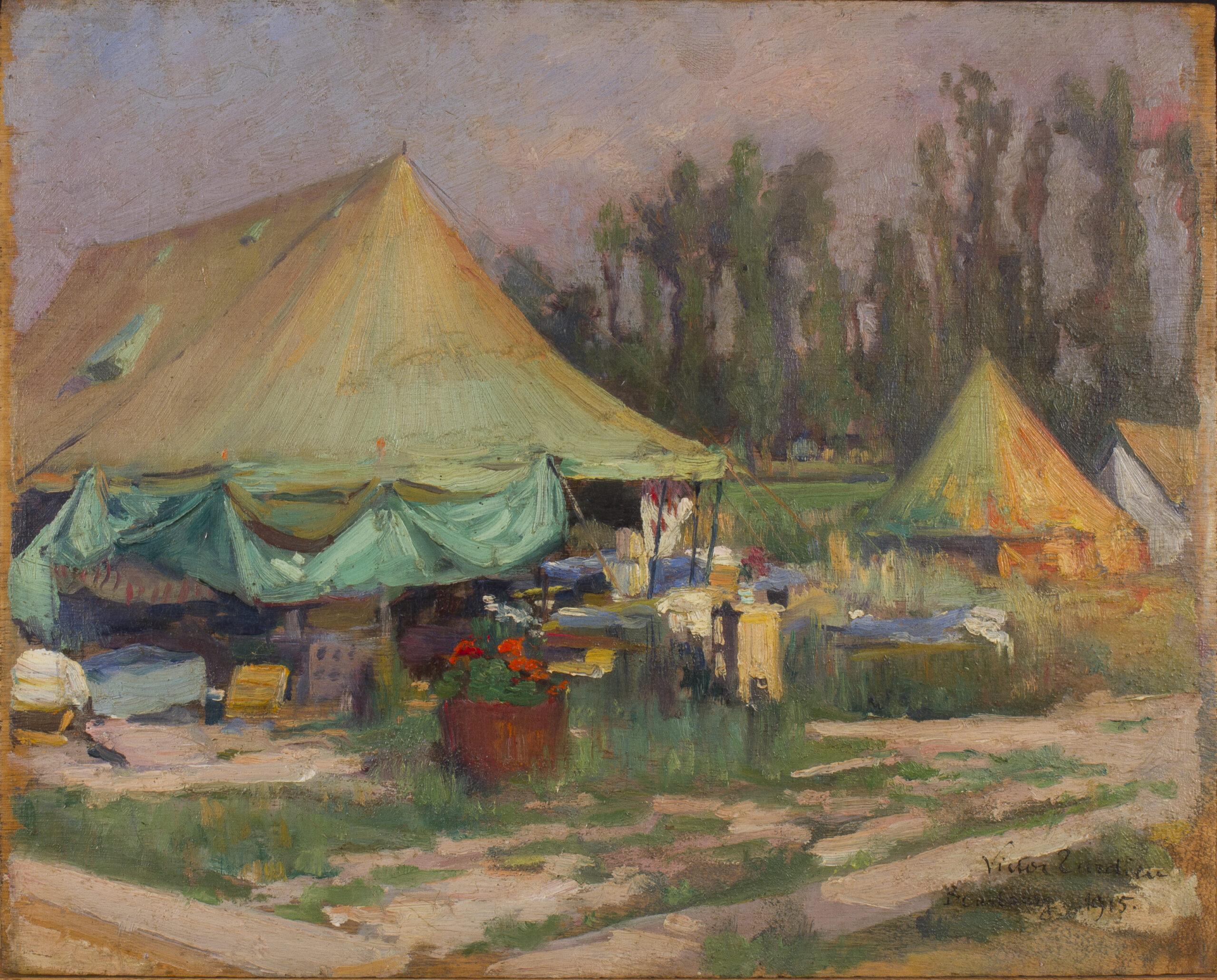

To mark the centenary of the First World War, the Florence Nightingale Museum honoured the role played by nurses in the First World War with a special temporary exhibition The Hospital in the Oatfield, which ran from March – October 2014. The exhibition showcased a set of ten oil paintings by French artist Victor Tardieu which depicted Millicent Sutherland’s field hospital in 1915. These paintings are now on permanent display in the main museum gallery.

The outbreak of hostilities in August 1914 prompted a huge increase in women volunteering for military service. Many joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) to become nurses, and these women – often from relatively protected backgrounds – worked closely with professional nurses who acted as mentors to the VADs. Even experienced peacetime army nurses were unprepared for the scale of the task facing them, and the threat of disease or injury was compounded by the ever-present risk of physical and nervous exhaustion. The nurses’ battle to save lives was as bitter as the warfare in the trenches, and the fields of France and Belgium witnessed the struggle not just with enemy soldiers, but against dirt, cold, terror and infection.

Society beauty Millicent Fanny St Clair-Erskine (1867-1955) was married to the Duke of Sutherland on her 17th birthday. After fulfilling her duty by producing four children, the Duchess devoted her all her time to entertaining and fundraising for worthy causes. She possessed a strong social conscience, which she applied to a series of campaigns aimed at achieving better working conditions in the Potteries near her husband’s estate in Staffordshire. Her interest in reform sat uneasily with some who saw her as an embarrassment, earning her the nickname ‘Meddlesome Millie’. In reality, her charitable work was highly practical and included training local women as midwives.

As soon as war was declared, the Duchess departed to France to establish an ambulance unit, the first of several such units to be set up by upper-class British women. Under the auspices of the French Red Cross, Millicent Sutherland, together with the surgeon Oswald Gayer Morgan and eight British nurses, travelled from Paris to Namur in Belgium in the late summer of 1914. Trapped under German occupation, she and her nurses escaped in a dramatic journey that she related in her autobiographical account, Six Weeks at the War.

Millicent Sutherland returned to France in October 1914 to set up a hospital of 100 beds at Malo les Bains near Dunkirk, which was transferred inland to Bourbourg in the spring of 1915 as the shelling along the coastline increased. Known to the locals as the ‘camp in the oatfield’, the hospital demonstrated the ingenuity of the nursing staff, who extended the shelter with brightly-coloured awnings borrowed from the many hotels along the Malo seafront. The camp was only three months in existence: at summer’s end, the hospital was moved to a series of huts in the dunes of Calais.

The French artist Victor Tardieu (1870-1937) is now best known for his role as founder and first director of the College of Art in Vietnam in the late 1920s. Despite his age, Tardieu volunteered for military service at the start of the war and was attached to the American Field Service, a volunteer ambulance driver unit. Although he initially had no official role as an artist Tardieu continued to paint, taking every opportunity that his duties and the weather offered. His work brought him into contact with Millicent Sutherland and her hospital in the oatfield.

Encouraged by the Duchess, he made a number of oil paintings of her field hospital, its patients and its nurses, which capture a moment of tranquillity amid the turmoil of the First World War. In these, we can see how the nursing of the wounded soldiers from the French and Belgian forces would have been aided by a beautiful rural setting. The paintings from Bourbourg, however, remained treasured personal possessions of Millicent Sutherland, a gift to ‘Madame la Duchesse’ from ‘un simple soldat’ and are now part of the permanent collection of the Florence Nightingale Museum.

Despite difficult conditions in hospital tents, trains and huts, soldiers were comforted and cared for, often at grave risk to the nurses themselves. Over 200 nurses in the British Army Medical Service lost their lives in the war; many of them volunteers working alongside professional nurses. The chances of a soldier surviving a wound would have been slim indeed without the dedication shown by these courageous women.